The International Bartenders Association, or IBA, maintains a list of official cocktails, ones they deem to be “the most requested recipes” at bars all around the world. It’s the closest thing the bartending industry has to a canonical list of cocktails, akin to the American Kennel Club’s registry of dog breeds or a jazz musician’s Real Book of standards.

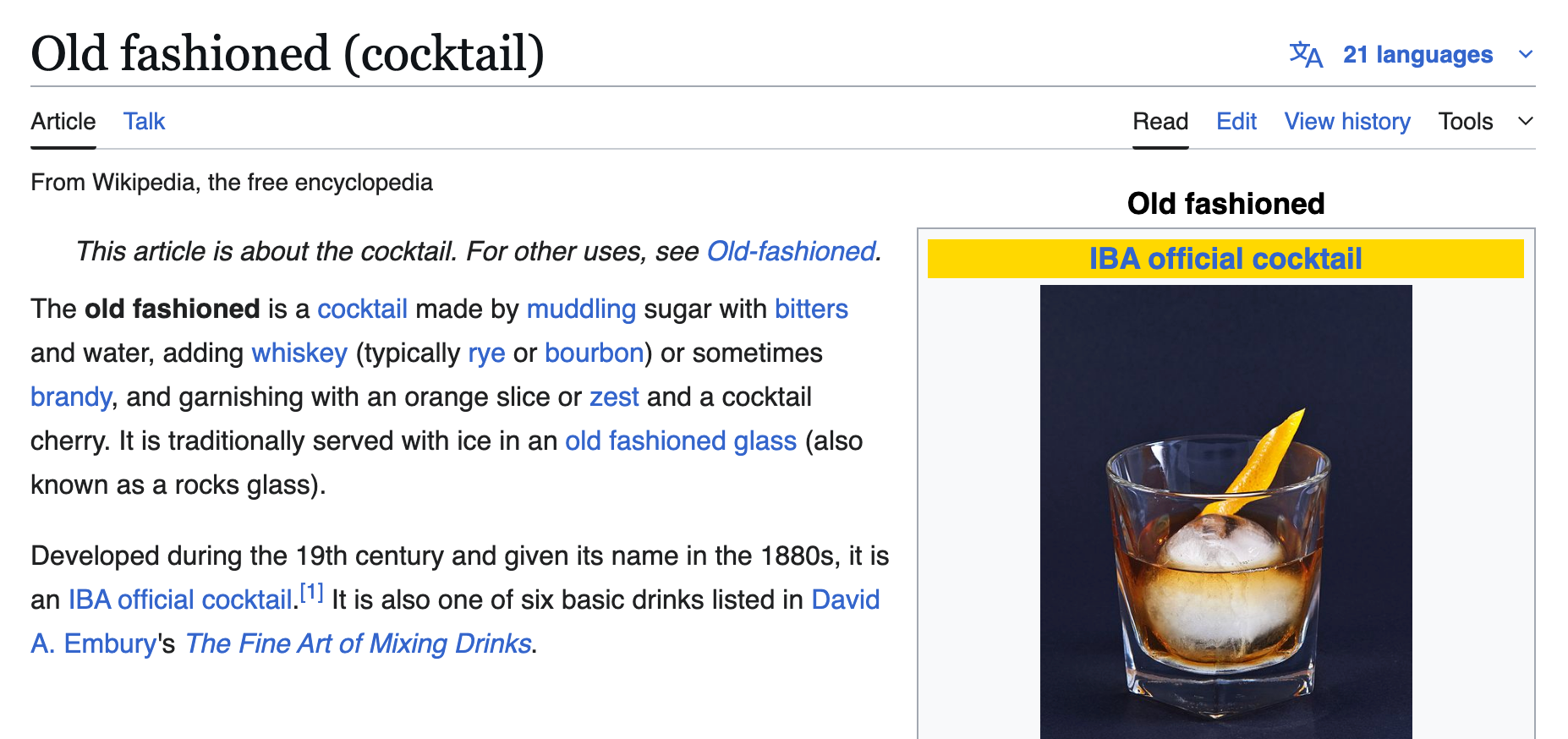

The IBA official cocktail list is the kind of list that has its own Sporcle quiz and its own Wikipedia article—an “IBA official cocktail” label even christens the top of each cocktail’s own Wikipedia infobox:

As of 2025, there are 102 IBA official cocktails, and as of July 12, 2025, I’ve had every one of them.

The journey has taken me to some interesting places, and now that it’s done, I have a little story to tell for each cocktail. I’m not gonna tell you all 102 stories, but I do want to debrief the experience. Drinking all 102 cocktails turned out to be unexpectedly tricky, and for reasons you’ll soon understand, I might be one of the first people in the world to do it.

⚠ Drink responsibly!

This endeavor involved drinking a lot of alcohol, but I did it over the course of a few years. It’s rare that I have more than a drink or two in one night (and never have I ever blacked out from drinking).

I do not recommend speedrunning the IBA official cocktail list. It’s important to know your limits, be conscious about how much you’re drinking, and drink a lot of water. If you’re struggling with an alcohol addiction, you should probably stop reading this post and talk to someone (if you’re outside of the US, you can find a helpline here).

How it started

I’m something of a list keeper. But it can be hard to decide when to start keeping track of things. So sometimes, I pick an arbitrary starting point that feels vaguely fateful, and I keep a list from that point on. For albums, it was the day I got my AirPods Pro delivered. For restaurants, it was the day I moved to New York City. For cocktails, it was the day I turned 21.

I started a note in Obsidian called Legal Cocktails, enumerating each type of classic cocktail I had consumed since I came of age. A dry martini at 5801 to usher in my birthday. A sex on the beach on an intern dinner cruise a couple weeks later.

Over the next couple years, Legal Cocktails grew to about 50 different drinks. Throughout my senior year at Illinois, my more epicurean friends Aidan and Christian would host a series of little get-togethers where they’d mix us drinks in their apartments, ranging from more pedestrian picks like the daiquiri and negroni to deeper cuts like the hanky panky and a half-decent Ramos gin fizz Christian made from melted butter.

First semester that year, I took a Beverage Management class, which was ostensibly about managing bars, but it was no secret that everyone took it because of its tasting component. The very last lecture focused on cocktails, and the tasting section featured an old fashioned, martini, margarita, whiskey sour, and the new-to-me Planter’s punch—not bad for a college class. And through it all, I was sometimes a normal college student, drinking Long Island iced teas at Legends happy hour and shitty tequila sunrises at Red Lion (I regret to inform you I deemed the Kams Blue Guy too proprietary for my list).

Some time after graduating and moving to New York City, I began to reckon with Legal Cocktails. What really counted as a “classic” cocktail? Where do I draw the line? It felt a little arbitrary. So on May 9, 2024, I decided to retcon the list into a checklist, and nix the “legal” requirement (something something statute of limitations). I had heard of the IBA official cocktail list from my time on Sporcle and Wikipedia, so it seemed like as good a list as any to base mine on.

At that point, there were 89 IBA official cocktails, and I had tried 33 of them (a bunch of the ones on Legal Cocktails weren’t IBA official, like the Jägerbomb and, weirdly, the amaretto sour). One thing was for sure: I had a lot of drinking to do.

Anatomy of a list

The IBA official cocktail list has existed for over 60 years. It was first proposed in Paris in 1960 by bartender and IBA founding member Angelo Zola, who felt the need to standardize the mess of cocktail recipes that differed depending on which bartender you asked. Zola assembled a committee within the IBA, and together, they decided on a set of cocktails that best represented the most important recipes served around the world.

The following year in Oslo, Zola’s vision became a reality, and the inaugural list was unveiled. It comprised 50 cocktails, many of which remain on the list today, but some of which (like the zaza) have gone by the wayside. That’s because the list has gone through big revisions every 10 years or so, with the IBA adding drinks they deem newly relevant and removing ones that have fallen out of fashion. (The 89-cocktail list I based my checklist on was established in the 2020 update.)

There are many ways one might organize a list of cocktails, but the IBA chooses to group them into three categories: the Unforgettables (these are all-time classics, like the Manhattan and the uhhh monkey gland), the Contemporary (these are newer, but have solidified classic status, like the Mai Tai and the Moscow mule), and the New Era (these are rising stars invented in the late 20th or early 21st century, like the espresso martini and the paper plane).

Most of the list comprises pretty normal cocktails that a good bartender would recognize. But some immediately struck me as esoteric, or hard to obtain for one reason or another—like the Canchanchara, which calls for Cuban aguardiente; the Spicy Fifty, an oddly specific recipe with red chili pepper in it; and what I saw as the final boss of the list, the Ve.n.to, with its arcanely formatted name and a recipe centered on grappa and a hyper-specialized “chamomile cordial.” All of them, nonetheless, had a Wikipedia page (no matter how small), their inclusion on the list alone serving as a badge of legitimacy.

I was slightly convinced the Ve.n.to was planted on the list by Big Grappa, and as far as I could tell, it was only served at one bar in middle-of-nowhere Italy (the Spicy Fifty, one in London). But I had a list to complete, and nothing was gonna stop me.

Smooth sailing

For a while, checking cocktails off the list was easy. It was just a matter of going to bars and restaurants (which, like any other yuppie, I was already doing), scanning the menu, and hoping to find a classic cocktail I hadn’t yet tried. A boulevardier at Kelly’s. A Champagne cocktail at Antler (one of my early favorites, a nice blend of bitters and bubbles).

A formative moment early in the quest came at Uncle Charlie’s Piano Lounge in Midtown with Ming and Alina. A divey gay bar with no menu? Sounded like a perfect opportunity to check off some drinks! I scanned through my list to find something simple to try and order, went up to a mustachioed bartender, and asked, “could you do a caipirinha?” He replied, “nah, we don’t have cachaça”—a reality check—and I said, “alright, I’ll just do uhhh an Aperol spritz” (one of my old reliables).

After crushing my spritz, I went back to the same bartender. Still determined to check some boxes, I asked for a mint julep. “I’m afraid we don’t have mint,” he laughed, “you fancy boy!” Unwilling to settle for another spritz, I scurried back to Ming and Alina and asked them what to do. Alina suggested, “why don’t you just show him the list and see what he can make?”

So that’s exactly what I did. Back at the bar, I briefly explained my mission to the bartender, handed him my phone, and he scrolled through the list. “Oh, I can do a few of these,” he said, “You’re cool with any of them?” “Yeah, whatever you can make,” I replied. Soon enough, I had a lemon drop martini in hand. (Alina tried mine and then ordered one for herself, but the bartender asked her, “Is that for your friend or you? If it’s for your friend I’ll make him something new!”)

After gleefully finishing the lemon drop (and singing “Y.M.C.A.” at the mic), I returned to the bar one last time. The bartender greeted me, “What’s next for you, fancy?” I handed him my phone again, told him to “surprise me,” and emerged with a New York sour, which he explained was basically a whiskey sour with a red wine float. Sometimes all you have to do is ask.

On our way out that night, the bartender bade me farewell—”bye, fancy!”—and I had a new favorite service experience of my life.

Monkeying around

The monkey gland, that one odd duck in the Unforgettables section, was my white whale for a while. Obscure even to a seasoned bartender, it taught me that you can’t go ordering every drink on the list willy-nilly. At another dive, my friend Michael went up to the bar and asked point-blank, “two monkey glands, please!” You could imagine the bartender’s confusion.

A month or so later, at Gage & Tollner with fellow cocktail enjoyer Malaika, we were bantering with the bartender about my list. He had also never heard of the monkey gland, but he was curious, so we explained it to him, and the conversation moved on.

Just as my rusty nail and Malaika’s French 75 neared completion, the bartender plopped down two cocktail glasses in front of us, each half-filled with a pinkish-orange liquid. “Two monkey glands,” he declared.

They were pretty good—the orange and anise flavors complemented each other surprisingly nicely, but also, they were free, which makes everything taste better.

London calling

I kept cruising through the list. A naked and famous at Death & Co. (where the naked and famous was invented). A Clover Club at the Clover Club (where, I learned, the Clover Club was in fact not invented).

Then in November, I was in London for a two-week work trip. This would mark a significant turning point in my journey, for multiple reasons.

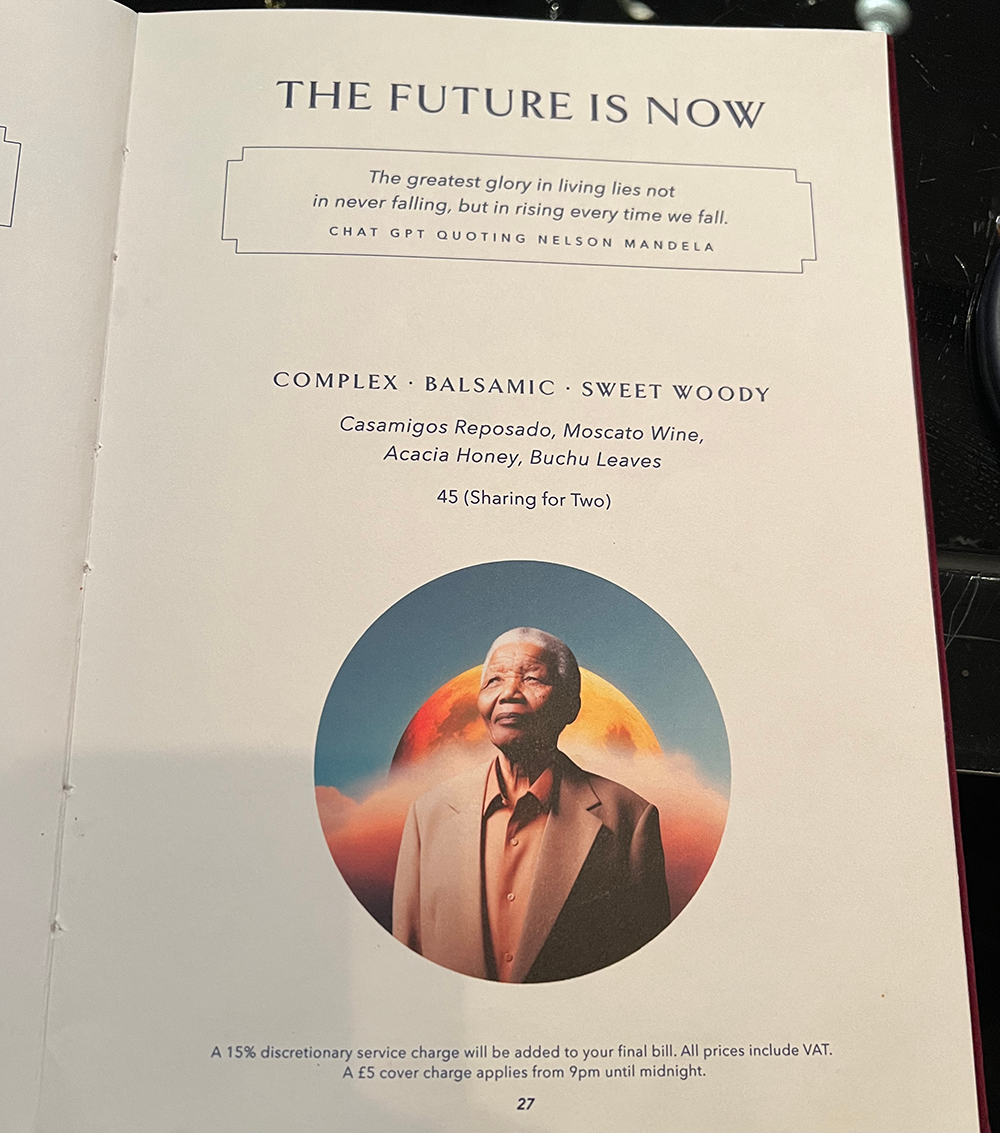

For one, I was able to check off the Spicy Fifty, one of the list’s most perplexing inclusions, by going to creator Salvatore Calabrese’s own Velvet bar at the Corinthia hotel, seemingly the only place in the world where it’s served. The bar was truly posh—before I had my drink (which was great, though I kinda wished it was spicier), I was greeted with a complimentary tray of candied almonds, olives, and blue corn flatbread. But this luxury was juxtaposed with an extremely cursed cocktail menu, featuring an AI-generated image for each drink (and one AI-generated Nelson Mandela quote):

I hit up the American Bar at the Savoy Hotel, London’s oldest extant cocktail bar, for an angel face (which was invented there) and a painstakingly garnished horse’s neck. I got a corpse reviver #2 at the confusingly similarly named Bar Américain. Turns out “American bar” just means a cocktail bar, as opposed to the city’s many beer-centric pubs, because cocktails are an American invention. That’s what I call a cultural victory.

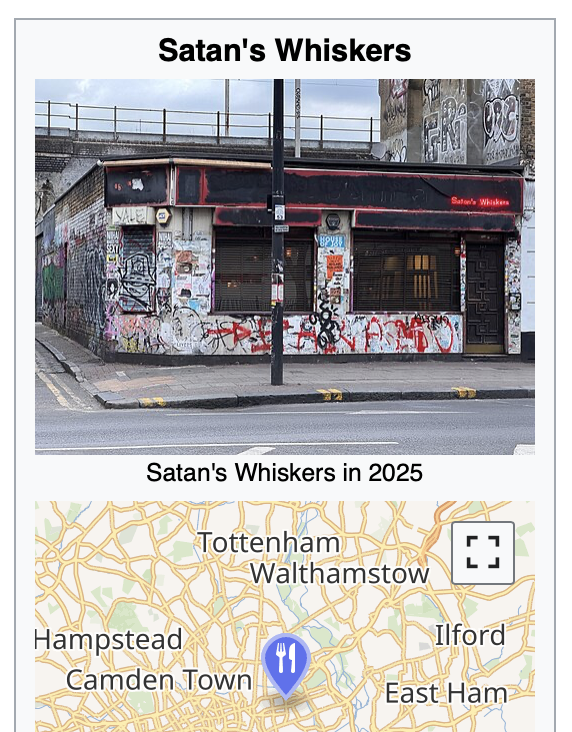

But the most important bar on this whole journey, and my new favorite bar in the world, was Satan’s Whiskers in London’s Bethnal Green neighborhood. I went there on a whim, per Malaika’s recommendation, not realizing it would be a godsend for someone trying to complete this list.

The thing about Satan’s Whiskers is that their printed menu, focused on classic and modern classic cocktails, completely changes every day. This means the bartenders have an encyclopedic knowledge of the cocktail canon, and they have the ingredients on hand to make any of the 900 drinks they rotate between.

At first, I scanned the menu and didn’t see anything I needed for the list, so I panic-ordered a Jungle Bird (which wasn’t on the list, but I had heard of it—it was great). Then I decided to venture off the day’s menu: “Do you know a… brandy crusta?” Without hesitation, the bartender Ollie said, “sure, I can do that!” and confirmed I wanted a sugared rim. Next, I had a Tipperary, which he explained was an odd flavor combination that they’d only really list on their menu on an unpopular day (Mia, another bartender walking by, chimed in, “Tipperary Tuesdays!”). I capped off the night with an Alexander—“gin or brandy?”—a brandy Alexander, which made for a perfect dessert cocktail. It all felt unreal, like a bar created in a lab for the sole purpose of me finishing this list.

A spanner in the works

A couple days later, I was checking in on the IBA official cocktail list website, and I could not believe my eyes. There were new cocktails on the list.

It felt like a bad dream. Still in an unfamiliar city, having just been to this magical bar, now confronted with these freaky new cocktail names on a list I had grown so accustomed to. Wasn’t the last update only a few years ago? (Since then, I’ve had several actual nightmares of the IBA adding anywhere from a few to a few hundred new drinks to the list.)

To be precise, there were now 102 IBA official cocktails, up from the previous 89. 3 had been removed from the list (including the golden dream, which I had gotten at Attaboy, long live the golden dream), and 16 new ones were added (including the Jungle Bird I had just had at Satan’s Whiskers, nice). I coped by tweeting through it, seemingly the first person on the internet to discover the update.

In reality, and I only learned this several months later, the day I discovered the update was the exact same day it was added to the IBA website. What I didn’t know was that there had been news articles about the update 8 months earlier, but they were all in Italian because the update coincided with a new 101 IBA Cocktails book, published exclusively in Italian for whatever reason (the book inexplicably leaves out the fernandito, fernet and Coke, maybe because 101 sounds more fun than 102).

It was no longer true that every IBA official cocktail had its own Wikipedia page. A few of the new ones did, like the sherry cobbler, the porn star martini, and the South Side (which had previously been added and removed from the list), but now the list was sprinkled with red links. Most of the new ones were pretty legit modern classics, but one stuck out like a sore thumb.

It was called, bafflingly, the IBA Tiki. A Google search revealed almost no information about it. Its recipe had 9 ingredients, including gengibre (just Portuguese for ginger) and two specific Havana Club rums, which are illegal in the United States thanks to Cuban sanctions. Step aside, Ve.n.to, there’s a new final boss in town.

I later learned that the drink’s recipe was commissioned by the IBA for their 2022 World Cocktail Championship, which was held in Cuba and, naturally, sponsored by Havana Club. For some reason, they saw fit to make it cocktail number 101 in their 101 IBA Cocktails book, and now it’s forever enshrined in cocktail history.

***

That night, I did the only thing I could do, and I went back to Satan’s Whiskers. In fact, I ended up going there four nights that week, checking off an obscene 13 cocktails within their taxidermied walls. The bartenders had, obviously, never heard of the IBA Tiki (and didn’t have those rums on hand), but they knew plenty of the other new additions off the dome.

It was also there that I discovered my love for the Porto flip, the only IBA official cocktail to contain egg yolk. I wasn’t sure if Satan’s Whiskers would be able to make one, but Mia’s face lit up when I ordered it—she had a soft spot for flips, and once I took a few sips, I knew it was one of my new favorites too. (On the Sporcle quiz, the Porto flip currently sits as the single least-guessed IBA official cocktail.)

I left London with a new favorite cocktail, a new favorite bar, and a napkin listing 6 bars Mia recommended in NYC.

82 down, 20 to go.

The final stretch

At this point, it was exceedingly unlikely to stumble upon the remaining cocktails on a bar menu. It was now a matter of seeking out particular bars that offered each drink, or failing that, going to really good bars and hoping they could whip one up.

Such was the case with one new addition, the Brazilian rabo de galo (literally “tail of the cock,” or “cocktail”), which I ordered off-menu at the bitters bar Amor y Amargo to excellent effect—I’ve since had two more of them at actual Brazilian restaurant Berimbau, and I’d easily place it next to the Porto flip as a favorite on the list.

I knocked out the Canchanchara at The Rum Bar BK, which miraculously had one on their menu. I got the new Chartreuse swizzle and pisco punch at the ice-obsessed Dutch Kills, which captures the Satan’s Whiskers magic as well as any bar I’ve been to in New York City.

I was this close to booking a trip to Italy for the Ve.n.to, when suddenly, googling “chamomile liqueur nyc,” I came across Santi, a new Midtown Italian restaurant that just so happened to have the exact right grappa and chamomile liqueur on hand. I went there with Alina, and the bartender, Emanuel, had never heard of a Ve.n.to, but he was determined to make me one—he even went on a wild goose chase to fetch a grape from the kitchen as a garnish, before coming back with some delicious vanilla poached pears. Impeccable service, tasty drink, and cheaper than a flight to Italy.

The last several drinks were more of a crawl than a sprint, many of them an exercise in explaining the recipe to a bartender in the least annoying way possible. An improvised paradise at Montréal’s Cloakroom. The very obscure Don’s special daiquiri at Paradise Lost. A Russian spring punch, a British creation I really should’ve gotten at Satan’s Whiskers, at Dear Irving.

And then there was one.

Let’s have a Tiki

Up until this point, I had acquired every cocktail by ordering it at a bar (or a makeshift bar at a friend’s apartment). But for the 102nd and final cocktail, the IBA Tiki, that wasn’t gonna work. Too obscure, too many ingredients, rums too illegal in the United States. So I took matters into my own hands.

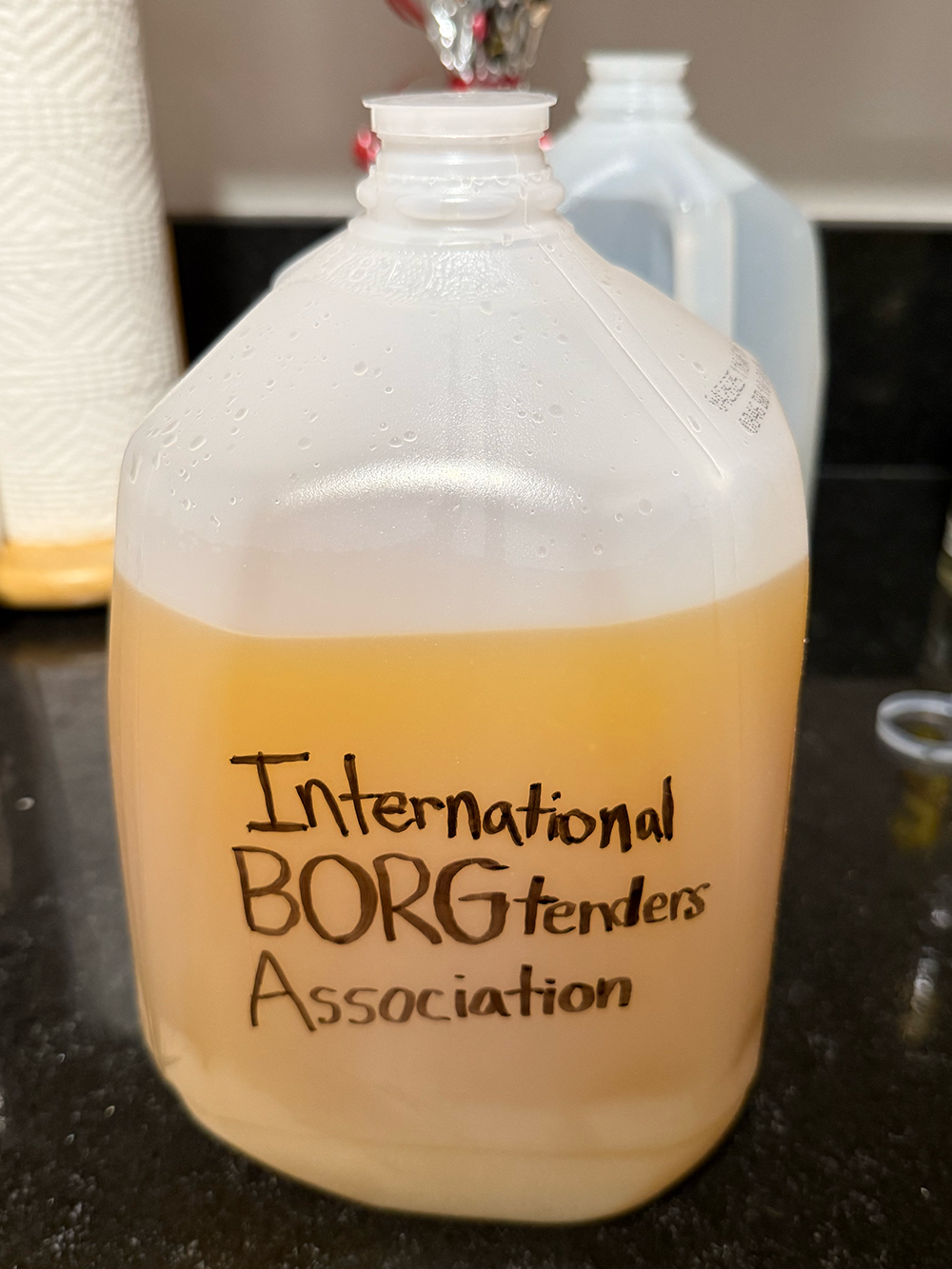

The plan: gather all the ingredients, batch-prepare some IBA Tikis, and throw perhaps the world’s first IBA Tiki party. Incidentally, my 24th birthday was quickly approaching, so I even had an occasion for the celebration.

The rums, of course, were the hard part. I can’t exactly explain what I did in a blog post, but let’s just say we were about to have some of the most faithful IBA Tikis that had ever been made in the United States. (Shoutouts to my mom and my sister, who both played instrumental roles in the operation.)

The rest of the ingredients were straightforward enough. Amaretto, check. Luxardo maraschino, check. Frangelico (hazelnut liqueur, which the IBA Tiki is the only IBA official cocktail to include), check. The juices and purée and gengibre, check. All that was left was to put it all together.

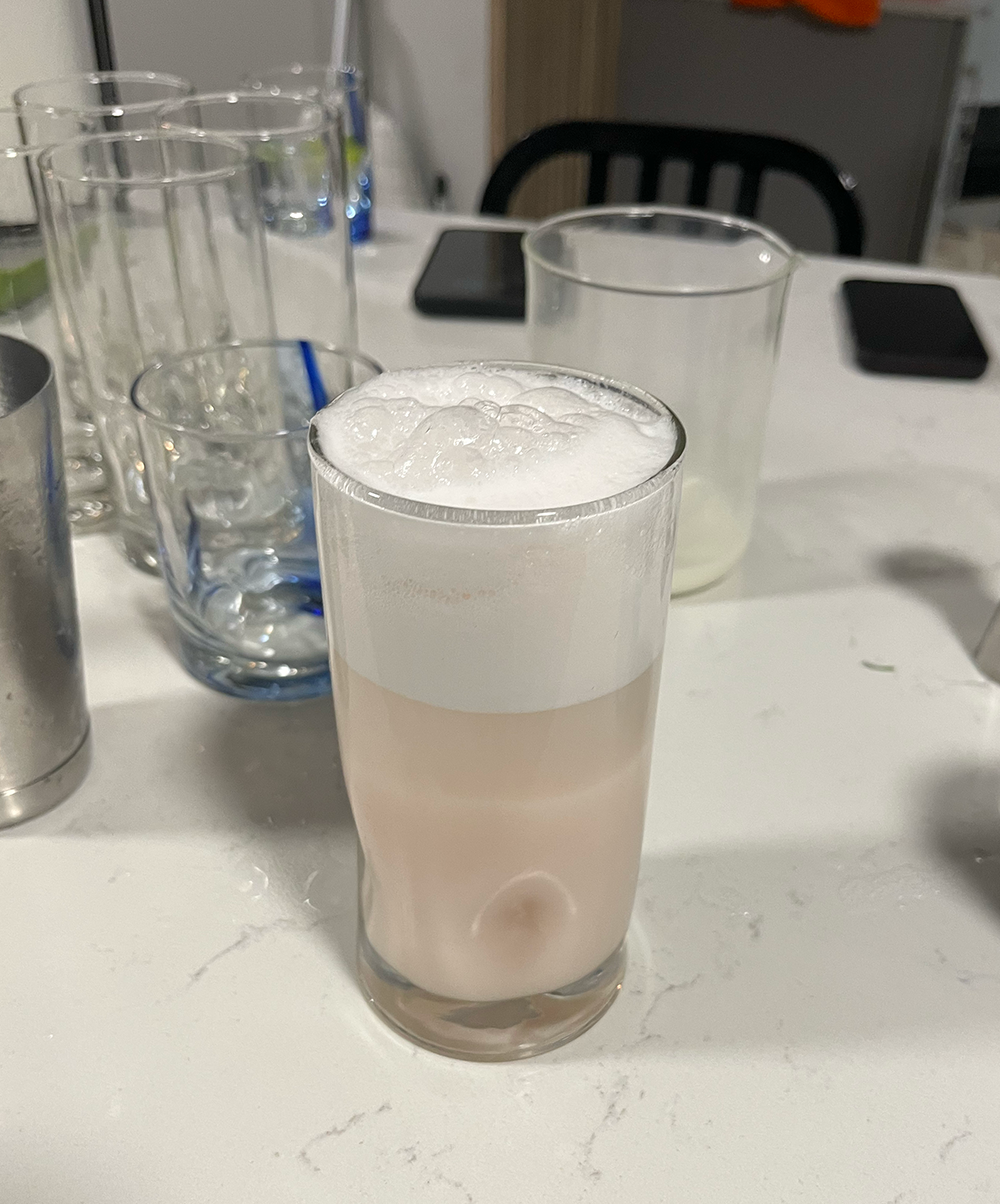

And so I did. On Saturday, July 12th, 2025, my 24th birthday, about 20 people gathered in a modest Brooklyn apartment. For the crowd, we prepared an industrial-sized IBA Tiki in the vessel of choice, a borg. But for my personal drink, I mixed it myself using a cocktail shaker my mom got me for my birthday, and I served it for myself in a highball glass. After carefully garnishing the cocktail (for the Wikipedia picture) and making a speech to the attendees, it was time to drink it.

The IBA Tiki was great. Everyone agreed it was great. It was sweet, sour, nutty, and gingery, and we went through two full borgs of it. It may be a completely contrived recipe, and it may or may not deserve to be on the list, but one thing’s for sure: it was a fitting end to the journey.

Closing time

102 cocktails, 7 states, 3 countries, and 1 surprise update later, my work here was done. But you can’t drink 102 cocktails without learning a few things along the way.

One thing I learned is that the IBA official cocktail list is a weird list. But that’s probably bound to happen when you try to represent the whole world of cocktails in one list. The list might be a helpful guide for a bartender aiming to be well-rounded, but in a practical sense, for normal people just going to bars and ordering drinks, it’s not all that useful.

So from my research and my interactions with dozens of bartenders, I recategorized the list into a spectrum based on name recognition and ingredient availability. It’s probably an oversimplification, and the perspective is definitely US-centric, but I think it makes for a good starting point if you’re wondering what to order:

Easy

Ingredients you can get at any bar

Medium

Ingredients that a good bar will have on hand

Hard

Rare, specialized ingredients

Well-known

Any decent bartender would know it

Medium

Skilled bartenders would know it

Obscure

Only a cracked bartender would know it

Between the Canchanchara, IBA Tiki, Spicy Fifty, Ve.n.to, and the relative obscurity of several others, you really have to be trying hard if you want to drink all 102. As far as I could find, no one else online has done so, at least not since the update that brought the IBA Tiki along. (It seems possible that someone high up at the IBA has tried one of everything, but I bet they made a lot of them themselves.) (Update after posting: it looks like some folks on Reddit have made their way through the list!)

When I first embarked on this journey, I didn’t really know what I liked in a cocktail. Now I know I like bitters, and egg whites, and silky, stirred drinks on a big rock. I’ve learned I have an affinity for Porto flips and rabo de galos. And I’ve learned that Satan’s Whiskers is the best bar in the world. (I also wrote its Wikipedia page, plus ones for the Jungle Bird, the Chartreuse swizzle, and the IBA Tiki. There’s still work to be done on many of last year’s additions!)

A common refrain at the IBA Tiki party was, “now that you’re done with cocktails, what’s next?” Well, I’ve gotten pretty good at drinking cocktails, but now that I have some mixology equipment, I might as well start making some. And while I’m at it, I can venture into the endless expanse of cocktails that aren’t on the IBA list.

I may be done with one list, but I’ll never stop checking boxes. I’m ambiently working my way through the NYT’s 100 Best Restaurants in New York City (18/100) and their 57 Sandwiches That Define New York City (18/57). I want to visit all 50 states (42/50) and all 63 national parks (12/63). Who knows, maybe I’ll try to pet every dog breed (???/292) or learn every tune in the Real Book (???/400).

But the IBA official cocktail list (102/102) is done and dusted. Until the next update, that is.